Inventory Number KLG199

Size 13.5" h x 20.25" w

Material Collotype

Period Secessionist

Country of Origin Austria

Year Made 1919

Plate #9, Funfundzwanzig Handzeichnungen, 1919, no. 289/500

Vienna, Gilhofer & Ranschburg, Publisher

25 collotypes in an edition of 500

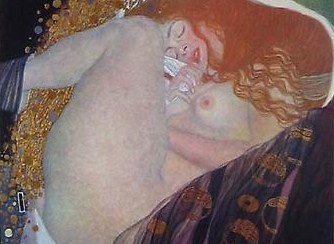

Fünfundzwanzig Handzeichnungen contains twenty-five monochrome and two-color collotypes after drawings by Klimt. It is as remarkable an achievement in collotype printing as the monumental Das Werk Gustav Klimts. Yet because the 1919 portfolio is based on drawings, its aesthetic achievement lies in capturing the variations of line that characterize Klimt’s drawing style between 1898 and 1917.

Whereas Das Werk Gustav Klimts demonstrated the collotype’s remarkable ability to render gradations of tone, color and texture in Klimt’s handling of paint, Fünfundzwanzig Handzeichnungen revealed the medium’s capacity for capturing his virtuosic use of the instruments of drawing. Thus the two portfolios can be viewed as embodiments of the contrasting poles that defined Klimt’s artistic production, the painterly and the linear.

Above all, Fünfundzwanzig Handzeichnungen reveals Klimt’s penetrating observation of women, from nubile youth to craggy old age. And his gaze is nothing if not penetrating, with the sexual overtones that word implies. Yet to label Klimt a voyeur seems trivial and reductive. His drawings reveal a profound identification with the female form, which seemed to release his creative energy, while their alternately flowing and darting lines demonstrate the flexibility of his technique. One need only compare the curvilinear precision of The Witch (1897) with the Rodinesque freedom of The Maiden (1912-13) to grasp the emotional and aesthetic range of Klimt’s line.

At the risk of stating the obvious, Klimt’s drawings of women are suffused with sexuality, although it is often unclear where the boundary between observation and identification lies. In drawings like Reclining Nude with Ruff (c. 1907) and Reclining Nude (1914-16), Klimt’s models seem to be simultaneously available for sexual scrutiny and lost in sexual reverie. This tension between self-presentation and self-absorption parallels the alternating roles of Klimt’s gaze, which vacillates between consuming and melding with the female body. It is this emotional fluidity that distinguishes Klimt’s erotic drawings from the banal realm of pornography, and creates an intense psychological reaction in the viewer. Perhaps this explains the almost irrational hostility expressed by critics when Klimt exhibited his erotic drawings at the Galerie Miethke in 1910 and at the International Exhibition of Prints and Drawings in Vienna in 1913. Klimt’s departure from the distanced idealization of female nudity in academic art clearly touched a raw nerve in Vienna, where women were typically either ignorant of or steeped in sexuality. Klimt’s portrayal of recognizable contemporary types, coupled with his refusal to distance himself from his subjects, provoked a hailstorm of abuse when he dared to exhibit erotic drawings in Vienna.

However, Klimt received a different critical response when he contributed fifteen erotic drawings to the 1907 book Dialogues of the Courtesans, a translation of the Hellenistic satirist Lucian by the poet Franz Blei (Blei himself chose the drawings from those in Klimt’s studio). In this sumptuous book, published in a limited edition of 450 copies, Klimt provided drawings of masturbating women and lesbian couples, images he could never have shown in public. Yet Dialogues of the Courtesans escaped critical censure, because it conformed to the category of amorous books and portfolios intended for an affluent, exclusively male audience.

In many ways Fünfundzwanzig Handzeichnungen conforms to the category of privately circulated erotic material that circulated amongst Vienna’s upper middle class men. Drawings like Two Girls (c. 1913) and Study for Water Serpents II 47 (1904-07) show women locked in lesbian embraces, while Portrait Sketch of Lady Wearing a Boa (c. 1905), Portrait of a Woman (c. 1906), and Standing Girl with Lace Headdress (c. 1906) depict the saucy süsse Mädel, the sexually independent young woman who earned her living by modeling for artists, or as mistresses to wealthy men like Arthur Schnitzler, who immortalized them in his famous literary works.

Given the care with which the drawings were chosen and printed, it seems likely that Klimt was involved in planning Fünfundzwanzig Handzeichnungen before his death in 1918. This hypothesis is bolstered by the lengthy time involved in producing high quality collotype plates especially for prints that required three plates for color separation (see Appendix: Technical Processes). The care with which the prints were made is evident throughout the portfolio: they are virtually indistinguishable from original drawings. Whether delicate or bold, Klimt’s line was faithfully rendered by the collotype process, enabling connoisseurs to own fine print versions of drawings that Klimt had long since ceased to show outside the privacy of his studio.